Investors are their own worst enemy. But what does that actually mean?

“Investors are their own worst enemy.” I’ve read or heard this a dozen times. Usually, I nod in agreement and pat myself on the back for sidestepping a trap that seems to catch just about everyone else.

For a long time, I didn’t give much thought to what this assertion meant in general, let alone in the sense of my portfolio. Then I thought about it for a long time. After that, I condensed my thoughts into the 3,000 or so words that follow. (Don’t worry; there will be plenty of pictures).

In short, I’ve been blissfully unaware of the numerous characteristics and tendencies that make investing so difficult. Among others, I am: overly confident, stubborn, easily influenced (though I believe that I am not), and very, very risk-averse. And none of these work in my favor.

Challenge #1: The ABCs

The ability to conduct objective, unbiased analysis is a key component of investing success. I had always assumed that executing on this idea — avoiding the external influences — is a relatively straightforward task. Just focus on what’s important, and don’t let biases impact my decisions.

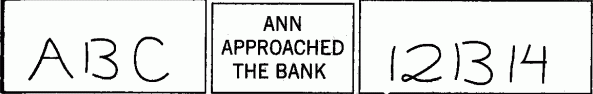

But my brain is wired to constantly consider context, allow influence from external factors, and generally jump to conclusions. The picture below, taken from Daniel Kahneman’s book Thought, Quick and Slow, shows this in action:

I read the left box as “ABC” and the right box as the numerical sequence “12 13 14” when I first saw it.

I didn’t realize what is now obvious: the middle character in both is exactly the same. My brain could have registered “A 13 C” or 12 B 14″ and been technically correct — but of course, it didn’t. Instead, it evaluated the character based on the surrounding information and made an automatic, split-second judgment.

This remarkable ability is, on the whole, a tremendous benefit. But it also demonstrates that I literally can’t read the alphabet without making unconscious decisions and allowing context to influence my interpretation of information.

I’ve always reassured myself that I was doing impartial, objective research when assessing possible investments. In fact, I was looking at the relevant data but also taking in everything around it, including the CEO’s presence, a bearish headline I’d seen earlier in the day, and a friend’s opinion. There has been a very direct and consistent result: where I should have seen two (or more) possibilities, I saw only one.

Challenge #2: Colors

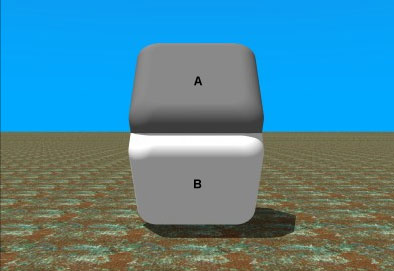

The image to the right is another classic illusion. When asked to determine the relative colors of the sides marked as A and B, I immediately identified A as darker — much darker. They are, of course, actually the same color (once I put a finger over the area where the sides intersect, this became obvious). My brain was duped by, among other things, its shadow experience.

This deception exposed a number of flaws. For instance, my brain was duped by prior experiences into thinking that such relationships can hold in a new situation.

Perhaps more important, however, was my failure to take the relatively easy steps that would have led to the correct answer. Once I arrived at what seemed to be a logical answer — after glancing for all of a second — I considered the exercise complete. I could have thought about the situation for a few seconds, approached the image from a few different angles, and reached a (correct) decision that was the opposite of my initial conclusion.

This is something I’ve done countless times while making investment decisions. After a sloppy analysis of the facts, I arrived at simple decisions, such as a bullish outlook on China and India’s emerging markets. Since I was more interested in a fast answer than an ideal one, I chose bond ETFs without really looking at what they hold. I came up with what seemed to be a rational response and went with it.

A better, more interactive demonstration of this tendency can be illustrated by playing the quick game below:

Challenge #3: Stubbornness

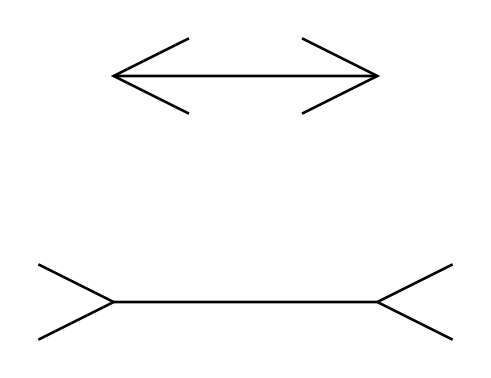

Consider the two lines shown to the right. By the time I saw this one, I could guess where it was going; the line in the bottom figure appears to be longer, but the two are actually the same size.

When I look at them again (or for the 100th time), the bottom one still looks longer — even though I know for a fact that it’s not. It has been proven to me beyond any possible doubt that the two are the same length. But my stubborn and easily fooled brain tells me otherwise. (I just looked again; that bottom line sure does look longer.)

As an investor, I’ve had a similar experience. While I knew (or at least strongly suspected) that a sell-off was unjustified, I panicked and sold anyway. Stock picking has been proven to be pointless (at least for someone with my abilities), but I can’t help myself (more on this below).

I’ve made a few investments over the years that turned out to be real dogs. After consistently blowing projections and missing deadlines, I still saw huge potential whenever I thought about the stock. It had been demonstrated to me over and over that the investment was a loser — but my brain still saw a sparkling opportunity.

Challenge #4: Hunger

The optical illusions presented above are amusing and, hopefully, humbling. (I’ll refrain from offering any more examples.) However, they are relatively pointless exercises; I thought that my brain was being misled because nothing was at stake (besides perhaps some personal pride). When it comes down to it, I’m sure I’d avoid those simple pitfalls.

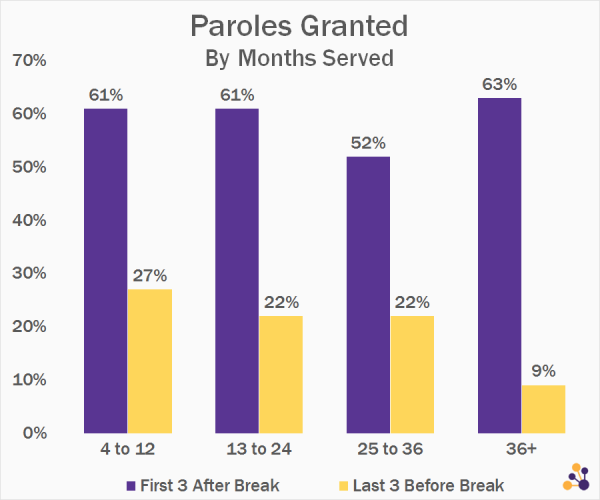

Several studies indicate otherwise. One notable project reviewed the decisions made by a group of experienced Israeli judges who considered parole requests all day. Twice a day, the judges took a break for food, which effectively segmented their period of work into three sessions.

When the data was analyzed, several predictable patterns emerged; for example, people who had never been incarcerated before were more likely to be given parole. Some patterns were less predictable, such as the difference in parole rates between the first three cases reviewed after a break and the last three cases reviewed before it.

These decisions weren’t quite life and death, but they were undoubtedly meaningful. The judges made very different decisions — that had profound impacts on the lives of others — depending on whether they were hungry and fatigued or full and refreshed. Portfolios checked right before lunch can receive hasty decisions and allocations, as I believe an examination of financial advisors will produce similar results.

My own portfolio upkeep has certainly been affected by my mental state; I prefer to tinker or rebalance in the evenings after a long day at work or on weekends when I have more pleasant tasks waiting for me when I finish. And, as a result, my decisions are probably impacted by my state of mind.

Challenge #5: Pretty Fonts

I like to think of myself as a perfectly rational being whose decisions are immune to the impact of outside factors. But, in fact, I am susceptible to even the most basic of deceptions. Find the following two statements:

- In the 1900 race, Theodore Roosevelt won the popular vote in all but five counties.

- In the 1900 race, Theodore Roosevelt won the popular vote in all but five counties.

These two statements are, of course, identical. They’re also false; Roosevelt was the candidate for vice president in 1900 and took over as president after William McKinley was killed. But I am more likely to believe statement #1 simply because of the font used. Bold styling, as well as the consistency of the print or the quality of the paper used, has been found to improve trustworthiness in related studies.

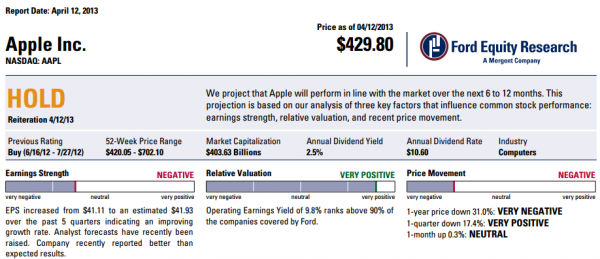

This vulnerability can be used in a variety of ways in the investment world. I trust analyst reports more than a comprehensive yet informative review on a random WordPress.com site, thanks to their clean graphics, vibrant maps, and 40-point “Outperform” or “Hold” conclusion.

A “Hold” rating on AAPL in the spring of 2013 was, of course, not a great call. But this report sure makes it look compelling.

Challenge #6: TVs and Computers

While I initially resisted (and am still resisting) the idea that fonts or the timing of my lunch impact major decisions, I would concede that the media I consume has some impact on my worldview. But I have generally believed the impact of the TV I watch or the websites I read to be minimal.

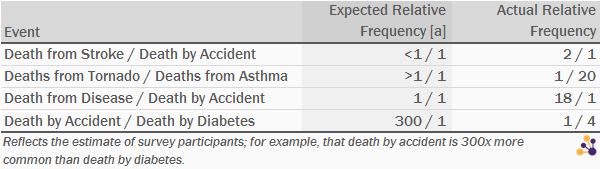

Participants in a study cited in Thinking, Fast and Slow were asked to estimate their chances of dying from different incidents such as a stroke, an accident, or diabetes. Participants consistently overestimated the likelihood of incidents that dominate news coverage (such as car crashes and tornadoes) while underestimating the likelihood of death from “uninteresting” causes, including cancer.

Most notably, death resulting from an accident was estimated to be 300 times more likely than death from diabetes — which actually claims four times as many victims.

Again, this error in judgment has obvious extensions to investing. I’m more likely to have optimistic feelings about stocks that are discussed regularly in the media, and I’m less likely to worry about companies that aren’t mentioned at all. I have an unrealized loss on Twitter (TWTR) as proof. My mom has asked for my opinion on Facebook (FB) and Apple (AAPL) stock but is yet to bring up Flowserve Corporation (FLS) or FMC Technologies (FTI).

I’m easily spooked by the stories that dominate the headlines — China stands out as a recent example — but never consider more serious risk factors that receive little coverage.

Challenge #7: Self Assessment

After confronting much of this evidence, I told myself that others may be susceptible to subtle manipulations from changes to the font or the news cycle but that such factors wouldn’t ever impact my decision-making. That probably isn’t the case; it’s much more likely that I suffer from illusory superiority.

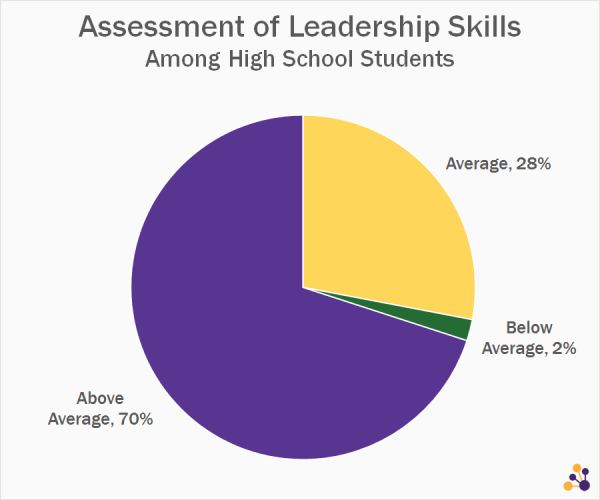

Countless studies have demonstrated that the majority of people judge themselves to be above average in a wide variety of categories ranging from driving ability to philanthropy. One classic study asked high school students to rate their leadership abilities, and the findings were as follows:

Data Source: College Board (1976-1977)

Data Source: College Board (1976-1977)

Other surveys also identified similar findings: motorcyclists believe they are less likely than the average biker to cause an accident (Rutter, Quine, and Albery, 1998); 94 percent of college professors rate themselves as “above average” (Cross, 1977); and bungee jumpers believe they are less likely than the average jumper to suffer an injury (Rutter, Quine, and Albery, 1998); and bungee jumpers believe they are less likely than the average jumper too (Middleton, Harris, and Surman, 1996).

This trend continues to the point of being almost comical: in one study, participants thought they were more likely than their peers to have correct self-assessments (Pronin, Lin, and Ross, 2002).

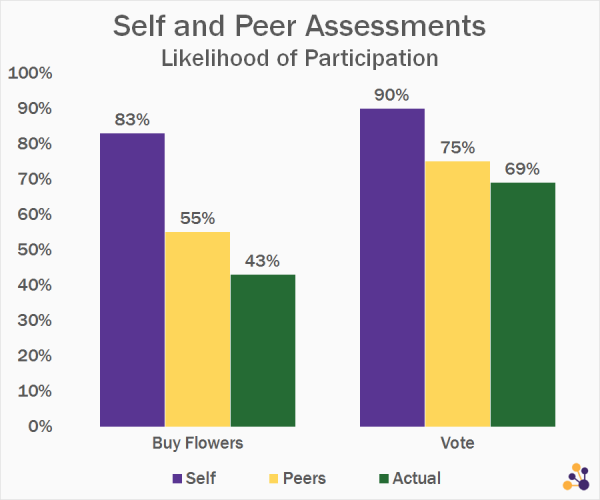

In another experiment, college students at Cornell were asked about an upcoming charity drive in which they could purchase flowers to benefit the American Cancer Society. More than 80 percent of the students predicted that they would buy flowers, but estimated that only 55 percent of their peers would. Similarly, 90 percent expected to vote in an upcoming election but expected only 75 percent of their peers to cast a ballot.

Actual participation was relatively easy to measure, so we have some amusing results.

Of course, the point of all of these studies is that it is human nature to exaggerate our own abilities. This has obvious implications for those who believe they are better stock pickers or asset allocators. (According to a 1998 report, stock pickers assume their picks are more likely to be winners than the average investor).

I’ve told myself many times that I’m a stronger stock picker than the average person (I have the TWTR place to prove it), that I knew when the markets were overvalued, and that I generally had superior insights. This idea of personal superiority is, of course, an illusion. And a costly one.

Challenge #8: Undeserved Optimism

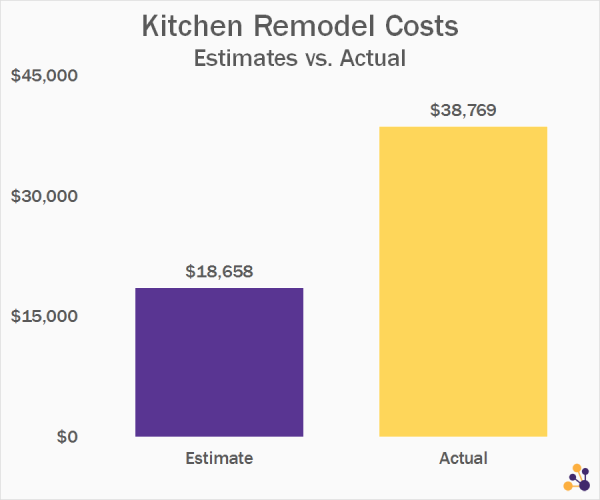

A 2002 survey referenced in Thinking, Fast and Slow asked homeowners to estimate the cost of remodeling their kitchen before the project began and then followed up totally the actual cost. The results revealed a tendency to dramatically underestimate expenses (and, conversely, to overestimate benefits):

Data Source: Cost vs. Value 2002 Report

Data Source: Cost vs. Value 2002 Report

I’m guilty of similar transgressions; I regularly underestimate the time taken to travel from point A to point B. (even when I make the same trip repeatedly). Even though I realized my previous estimates were poor, I underestimated the cost of the last few vacations I took. I make a best-case scenario assumption and disregard information that contradicts my desired outcome.

When it comes to saving, this fallacy may have some clear (and unfavourable) implications. I’ve flipped through StockTwits commentary for a stock I own several times (most recently RNDY). Each bullish viewpoint increases my trust in my decision, but bearish viewpoints are usually dismissed and ignored. I wouldn’t put much trust in the bears’ opinions; they must be jealous or confused! These RNDY bulls, on the other hand, are incredibly astute — congrats on getting in on this one!

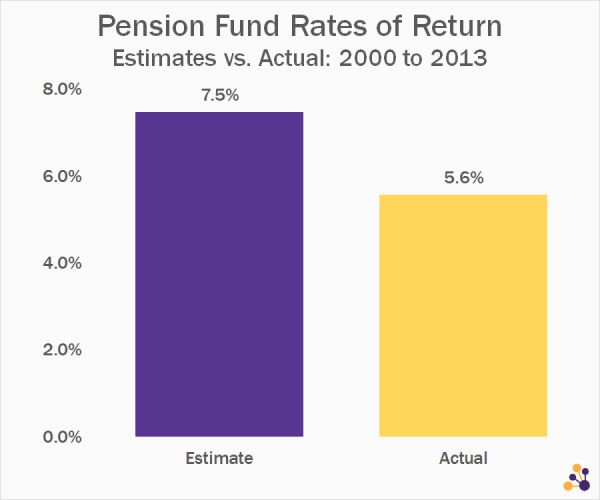

Many pension funds are in dire straits as a result of decades of excessively optimistic (and obviously unreasonable) projected rates of return: I have some well-heeled business as a victim of the planning fallacy:

The data is based on the top 100 funds, which have a total asset value of $1.3. Data Source: Milliman

Challenge #9: Procrastination

Procrastination is a natural human trait. This isn’t a novel idea. Procrastination is relatively harmless in most domains; I had a horrible December 23rd at the mall, where I paid for a few subscriptions I no longer used, but the costs were negligible. Procrastination, on the other hand, can be very expensive in the realm of investing.

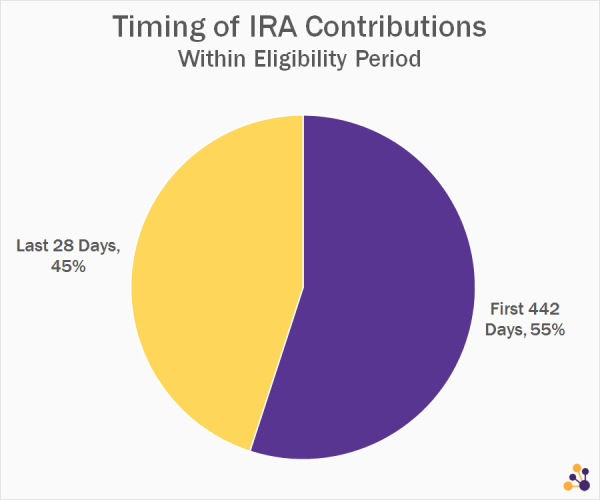

Contributions to IRAs are perhaps the best example. Each year’s contribution duration is 470 days long, from January 1 to April 15 of the following year. The following is how Fidelity breaks down the timing of these contributions, which are an essential aspect of many retirement plans:

In the four weeks leading up to the deadline, nearly half of all submissions are made (and I suspect many of those come in the final week). This occurs despite the fact that there can be significant opportunity costs associated with remaining on the sidelines for 442 days over the span of a typical “saving era” timeline.

Even though the adequate hourly pay for doing so on time was likely well over $500, I made many April 15 IRA contributions and waited months to roll over a 401(k) into a cheaper IRA.

Challenge #10: Statistics

One of the first books on investing I read was Burton Malkiel’s A Random Walk Down Wall Street. But I still struggle to incorporate a proper understanding of the concept of “random” into my tasks as an investor.

Assume a coin is tossed ten times, with each toss resulting in a head or tail outcome. Consider the following three possible outcomes for this sequence of tosses:

- HHHHHTTTTT

- HHHHHHHHHH

- THHTHTTHHH

- Non Gamstop Casinos

- Best Payout Online Casinos

- Migliori Casino Online

- Casino En Ligne

- Online Casinos

When asked which of the three sequences was most likely to be the outcome of a random toss, the third sequence was the obvious choice. The first two are clearly patterned, while the third appears to be random. Of course, in a completely random sequence of tosses, the odds of all three results are exactly equal.

I have repeatedly confused random outcomes with skill. I have interpreted a series of winning stock picks as indicative of talent rather than the toss of a coin. I was astounded by one mutual fund that outperformed the market for five years in a row, despite the fact that this is a fairly normal occurrence (1 in 32 chance) if annual outperformance is perfectly random. Many who predicted major events (such as the 2008 financial crisis) without questioning whether their prediction was a fortunate one sandwiched between various losers also impressed me.

Challenge #11: Risk Aversion

Several years ago, I learned about the concept of risk aversion in a Finance 101 class. When markets crumbled in 2008, I gained a deeper understanding of the concept. A few basic hypothetical situations can ideally boost the textbook concept.

Assume you have the ability to play a game with the following outcomes:

- I win $105 if the coin lands on Heads; or

- I lose $100 if the coin lands on Tails.

My gut tells me to pass, even though a positive expected payout is easily calculated. Most survey participants are in the same boat and would require the winning payout would need to be closer to $200 before they take a toss. The number my gut comes up with isn’t too far off from that.

Another hypothetical scenario demonstrates my aversion to risk: suppose you have a choice between two options:

- 90% chance of winning $100 and a 10% chance of winning nothing; or

- Guaranteed $85.

Even though I know my estimated payout from the other option is higher, I’d take the $85. The remote probability of winning nothing and the resulting regret terrifies me.

Consider my natural reaction to these statements. In both cases, my reaction was to pick the option with the lower expected payout. The game is rigged in my favor, and I still choose to pass. I don’t like the idea of losing $100 or of having regret of missing out on $85.

This is a very simplified reason for panic selling after a significant market drop: I decide not to play the game with winning odds because I’m afraid of losing a large amount of money. My normal wiring is once again at odds with statistics and logical thinking.

Challenges #12 to #100

I’ve probably simplified many of the examples above, and I’ve certainly only scratched the surface of my flaws as a human attempting to be a rational investor. But hopefully, you might’ve received the general message, and my blunders will stop you from making any of your own.

After describing my investing follies in great detail, I believe I am uniquely qualified to provide the following piece of advice:

- Tune out the noise. There is a lot of crap out there. Ignoring it is much easier said than done, but it’s also incredibly rewarding.

- Read. In addition to the junk, there is a tremendous amount of quality information as well. The amount of time that the community at Bogleheads.org has spent offering thoughtful, free advice should single-handedly restore at least a bit of your faith in humanity. Jason Zweig’s archives are another free gold mine. Some other thoughtful professionals, in no particular order, include Meb Faber, Morgan Housel, Noah Smith, Bill Schultheis, Ben Carlson, Bob Seawright, Patrick O’Shaughnessy, Tom Brakke, Michael Batnick, and Cullen Roche.

- Read…actual books. I started down the path of this article after finishing Thinking, Fast and Slow. I recommend that title specifically, but there is no shortage of worthwhile reads. Sometimes investing insights come from the most unexpected places. (Both Patrick O’Shaughnessy and Meb Faber are excellent sources of recommendations.) Warren Buffett reports that he spends 80% of his workweek reading and thinking; if he still has too much to learn, mere mortals may as well.

- Get help. I’ve generally been skeptical of the wealth management industry, but only because I know how it actually works. There are, of course, some exceptions to the rule in the form of truly excellent and honest advisors. I have a lot of respect for both Rick Ferri of Portfolio Solutions and the duo of Josh Brown and Barry Ritholtz at Ritholtz Wealth Management, as well as Cullen Roche and several of the other folks mentioned above. They probably aren’t personally immune from all of these flaws but have spent a lot of time developing systems that are.

I’d love to hear your thoughts and experiences; please continue the discussion below.

Leave a Reply